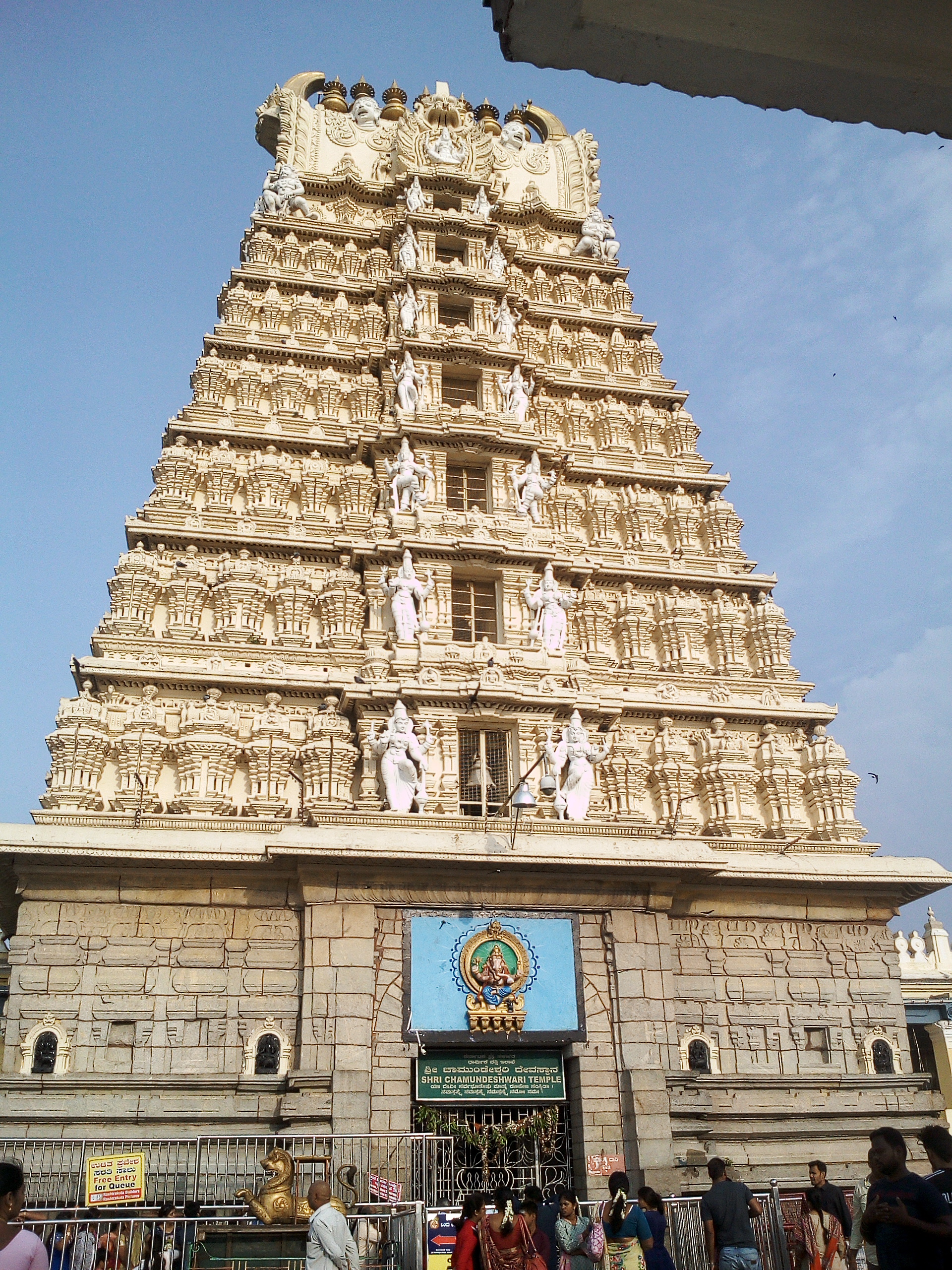

Chamundesvari Temple, Mahabalesvara, India

Devasyapratimah, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

Devasyapratimah, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

India’s identity is deeply shaped by its temples, which stand not just as places of worship but also as testaments to artistic ingenuity, spiritual philosophy, and cultural continuity. Hindu temple architecture in India is one of the most remarkable architectural traditions in the world, blending symbolism, engineering, and devotion in every detail.

From the towering shikharas of North India to the intricately carved gopurams of South India, Hindu temples embody the eternal link between the divine and humanity.

This essay explores the types of Hindu temple architecture, the historical invention and evolution of these styles, the structural divisions of temples, how they have survived across centuries, and what makes them so special and unique even today.

If any tourists need any help, here is the official website of the Government of India to guide the domestic and foreign tourists: India Tourism Development Corporation (ITDC)

Origins of Hindu Temple Architecture

The earliest Hindu shrines were simple structures built of perishable materials such as wood, clay, or brick. With time, as religious practices evolved, permanent structures of stone began to be built, especially around the 4th century CE during the Gupta period, which is often called the “Golden Age of Hindu Architecture.”

The invention of temple styles was heavily influenced by:

-

Vedic traditions, which emphasized sacred spaces for fire rituals (yajnas).

-

Cosmology and symbolism, as temples were designed as microcosms of the universe, representing the body of the deity and the cosmic order.

-

Regional influences, such as geography, climate, and local culture, shaped construction styles in different parts of India.

Thus, Hindu temple architecture developed into several schools, yet all shared a common vision: to create a sacred space where humans could commune with the divine.

Major Types of Hindu Temple Architecture in India

Hindu temples across India fall primarily into three broad categories, though many sub-styles and hybrids exist.

1. Nagara Style (North India)

-

Found predominantly in northern, western, and central India.

-

Characterized by the shikhara—a curvilinear tower rising above the sanctum (garbhagriha).

-

The plan is generally square with projections, giving the temple a cruciform shape.

-

No elaborate gateways; the emphasis is on the central tower.

-

Examples: Kandariya Mahadev Temple at Khajuraho, Sun Temple at Modhera, and the temples of Odisha like Konark.

|

| Mamichaelraj, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Meenakshi Temple-North Tower |

2. Dravida Style (South India)

-

Flourished mainly in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana.

-

Recognizable by its pyramidal vimana (tower above the sanctum) and monumental gopurams (gateway towers).

-

The temples are enclosed within massive walls, forming a temple complex.

-

Richly adorned with sculptures depicting gods, goddesses, and mythological scenes.

-

Examples: Brihadeeswarar Temple at Thanjavur, Meenakshi Temple at Madurai, and Virupaksha Temple at Hampi.

3. Vesara Style (Deccan / Hybrid)

-

Emerged in the Deccan plateau, combining features of Nagara and Dravida.

-

Towers may have curvilinear as well as stepped forms.

-

Temples often have star-shaped plans and ornate carvings.

-

Flourished under the Chalukyas, Hoysalas, and Rashtrakutas.

-

Examples: Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu, Chennakesava Temple at Belur, Kailasa Temple at Ellora.

Other Regional Variations

Beyond the three main types, several regional variations exist:

-

Odisha Temples—Known for their distinctive rekha deul (tall sanctum tower) and jagamohana (assembly hall). Example: Lingaraja Temple at Bhubaneswar.

-

Khajuraho Temples—Famous for their ornate sculptures and sensuous carvings.

-

Kashmir Temples—Reflect influences from Central Asia and Gandhara styles.

-

Northeast Temples—Assam’s Kamakhya Temple is an example, with domical structures influenced by local traditions.

Survival of Hindu Temple Architecture

Hindu temple styles have survived across centuries despite invasions, natural decay, and social changes. Their endurance can be attributed to:

-

Stone Construction—Using granite, sandstone, and marble ensured longevity.

-

Symbolic Rebuilding—Temples destroyed by invaders were often rebuilt, as the idea of the temple was eternal.

-

Royal Patronage—Kings and dynasties considered temple building as acts of dharma, ensuring continued construction and preservation.

-

Community Devotion – Local communities actively preserved temples as cultural and religious centers.

-

Modern Conservation Efforts—The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and UNESCO World Heritage recognition have played vital roles.

Structural Divisions of Hindu Temples

Despite regional variations in style and scale, most Hindu temples share a fundamental symbolic and functional structure. This structure is not arbitrary—it reflects the spiritual journey of the devotee from the outer material world into the sacred inner realm of the divine. Every element, from the gateway to the crowning spire, carries deep philosophical meaning while also serving practical purposes. The temple, in essence, is a three-dimensional representation of cosmos, body, and consciousness.

Below, we explore each of the major divisions of a Hindu temple in detail.

|

| Entrance gateway of CHAMUNDESWARI TEMPLE, MYSURU JAGANNATH MAHAPRABHU 2006, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

In South Indian temples, the gopuram is often the first feature a visitor encounters. These monumental entrance towers soar above the temple complex, sometimes reaching heights of over 200 feet. Painted in vibrant colors and covered with countless sculptures, they serve as both a physical gateway and a symbolic threshold between the secular world outside and the sacred realm within.

Each gopuram is usually adorned with mythological depictions—stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas are carved in exquisite detail. The figures often include gods, goddesses, celestial beings, and demons, visually narrating the eternal struggle between good and evil. In addition, musicians, dancers, and scenes of daily life appear, symbolizing the integration of worldly existence with the spiritual journey.

The gopuram has a practical role as well: in large temple towns like Madurai or Srirangam, it acts as a landmark, guiding pilgrims from miles away. Its sheer scale reflects the grandeur of the divine, reminding devotees that they are approaching a power greater than themselves. Passing through the gopuram is, therefore, more than entering a building—it is an act of crossing from the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Lengthy corridor of Sri

Ramanathaswamy temple, Rameswaram

Vensatry, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mandapa (Assembly Hall)

Ramanathaswamy temple, Rameswaram

Vensatry, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

After the entrance, devotees typically enter the mandapa, a pillared hall that acts as the heart of the communal temple experience. Mandapas serve as spaces for gathering, prayer, singing devotional hymns, listening to religious discourses, and even witnessing performances of classical dance or music.

They embody the principle that spirituality is not confined to solitude but is also celebrated in community.

Architecturally, mandapas are often marvels of craftsmanship. The ceilings may be adorned with intricate lotus motifs, representing spiritual blossoming.

The walls and pillars frequently depict episodes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and other sacred texts, carved with astonishing finesse. These carvings were not merely decorative but educational, serving as visual scriptures for devotees, many of whom were illiterate in earlier centuries.

Some temples have multiple mandapas, each serving a specific purpose. For instance:

-

Ardha-mandapa: an entrance porch connecting the gopuram to the inner hall.

-

Maha-mandapa: the great hall for large gatherings.

-

Natyamandapa: a hall designated for dance and cultural performances dedicated to the deity.

By moving through the mandapa, devotees symbolically prepare themselves—mentally and spiritually—for their approach to the sanctum.

Garbhagriha (Sanctum Sanctorum)

At the heart of every Hindu temple lies the garbhagriha, or sanctum sanctorum. The word literally translates to “womb chamber,” reflecting its role as the source of divine energy and creation. Unlike the expansive outer halls, the garbhagriha is deliberately small, dark, and austere. This architectural choice is intentional—it represents the inward journey of the soul, away from distractions, into the core of consciousness where the divine resides.

Within the sanctum rests the murti (idol or image) of the presiding deity, consecrated through elaborate rituals that infuse it with divine presence. Devotees approach with reverence, often after waiting in long queues, to receive darshan—the sacred act of seeing and being seen by the deity. The atmosphere is hushed and intimate, contrasting with the vibrancy of the mandapa outside.

In symbolic terms, the garbhagriha represents the heart of both the temple and the devotee. Just as the human body houses the soul, the temple houses the divine essence. The temple priest alone usually enters the sanctum to perform rituals, while devotees experience the sanctity from its threshold.

Dwarkadhish Temple, at Dwarka, Gujarat, India

Kunalmehra7, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Shikhara / Vimana (Tower Above the Sanctum)

Kunalmehra7, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Rising above the garbhagriha is the tower, which varies in form depending on regional style. In the Nagara style of North India, the tower is called a shikhara, curving gracefully upward like a mountain peak.

In the Dravida style of South India, it is known as the vimana, built in stepped pyramidal layers.

Regardless of style, this vertical element symbolizes Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain described in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain cosmology as the axis of the universe. The upward movement of the tower signifies the soul’s ascent toward liberation and unity with the divine.

The tower also serves as a beacon—visible from great distances, it reminds communities of the ever-present divine in their midst. Some shikharas, such as those at Khajuraho, are clustered in groups, representing mountains encircling a central peak. This imagery reinforces the idea of the temple as a sacred landscape where earth meets heaven.

Pradakshina Patha (Circumambulatory Path)

Surrounding the sanctum is often a pradakshina patha, or circumambulatory passage. Devotees walk clockwise around the garbhagriha, keeping the deity to their right side, a gesture of reverence and surrender. The act of circumambulation reflects the cosmic order, echoing the movement of planets around the sun and reminding devotees of the centrality of the divine in their lives.

This practice also symbolizes introspection. As one walks in circular motion, repeating prayers or mantras, the mind gradually quiets, preparing for deeper spiritual connection. In larger temples, there may be multiple concentric paths, allowing thousands of pilgrims to perform pradakshina without disturbing the sanctum.

Amalaka and Kalasha (Crowning Elements)

At the very top of the shikhara or vimana rest two distinctive features: the amalaka and the kalasha.

The amalaka is a large, ribbed stone disc resembling the fruit of the amla tree. It symbolizes completeness, the eternal cycle of life, and the sustaining power of the cosmos. Its circular form serves as a stabilizing feature, visually separating the ascending tower from the crowning finial.

Above the amalaka sits the kalasha, a pot-like structure often gilded or made of metal. In Hindu symbolism, the kalasha represents abundance, fertility, and auspiciousness. In ritual contexts, the kalasha is filled with water or grains and placed at the start of ceremonies to invoke divine blessings. On the temple, its position at the highest point signifies the ultimate goal of human life: reaching the pinnacle of spiritual fulfillment.

Together, the amalaka and kalasha complete the vertical symbolism of the temple, guiding the devotee’s gaze upward from earth to sky, from materiality to transcendence.

Conclusion

The structural divisions of Hindu temples are not merely architectural features; they are spiritual milestones in a sacred journey. From the vibrant gopuram that welcomes pilgrims, through the mandapa that fosters community, into the garbhagriha that houses divine presence, and finally upward to the shikhara crowned with amalaka and kalasha, the entire temple is a cosmic map.

Each section embodies philosophy, science, and art, transforming stone into a living representation of the universe. By walking through the temple, devotees enact the transition from the outer material world to the inner spiritual self, culminating in communion with the divine.

Thus, Hindu temples are not simply buildings—they are embodied philosophies, timeless bridges between human beings and cosmic truth.

Symbolism and Special Features

Hindu temples are unique not merely for their architecture but for their deeper symbolism:

-

Cosmic Representation—Temples represent the universe, with the sanctum as the cosmic womb.

-

Alignment with Nature—Many temples are aligned with cardinal directions, solstices, or river flows.

-

Sculptural Narratives—Walls are adorned with depictions of gods, goddesses, mythical beings, dancers, and musicians, blending spirituality with everyday life.

-

Mathematical Precision—Proportions are guided by Vastu Shastra (ancient architectural science), ensuring harmony and balance.

-

Integration of Arts—Architecture, sculpture, music, and rituals come together in temples, making them holistic cultural centers.

Why Hindu Temples are Special

Hindu temples are more than architectural marvels—they are:

-

Centers of Spiritual Energy—Believed to be spaces where divine energy is concentrated through rituals and consecration.

-

Cultural Hubs—Festivals, dances, and music performances are integral to temple life.

-

Educational Institutions—In ancient times, temples were centers of learning in philosophy, astronomy, and medicine.

-

Community Spaces—Temples foster unity, as people of all backgrounds gather for devotion and celebration.

-

Timeless Inspirations—The beauty of temples continues to inspire artists, architects, and spiritual seekers worldwide.

Challenges in Preserving Temple Architecture

Despite their resilience, Hindu temples face threats:

-

Environmental Damage—Pollution and natural weathering erode stone surfaces.

-

Urban Encroachment—Modern construction near temple sites threatens their sanctity.

-

Neglect and Looting—Some lesser-known temples suffer from neglect or theft of idols.

-

Mass Tourism—While beneficial, unregulated tourism can damage delicate carvings.

Conservation efforts, heritage awareness, and responsible tourism are crucial for safeguarding these treasures.

Hindu Temple Architecture as a Global Heritage

Temples like Khajuraho, Hampi, and Brihadeeswarar have been recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, drawing global admiration. Scholars, architects, and travelers from across the world marvel at the ingenuity of ancient Indian artisans. For foreign tourists, Hindu temples offer not only a glimpse into spirituality but also lessons in art, history, and sustainable design.

The temple tradition, while deeply rooted in Hindu philosophy, transcends religion to become a universal symbol of human creativity, devotion, and the search for the divine.

Conclusion

The architecture of Hindu temples in India is a magnificent journey through time, faith, and artistry. From the curvilinear shikharas of Nagara temples to the towering gopurams of Dravida shrines, from the hybrid Vesara marvels of the Deccan to the unique regional variations, each style narrates a story of devotion and innovation.

These temples were not just constructed as buildings but as cosmic diagrams, guiding devotees from the external world into the inner sanctum of consciousness. Their survival across centuries speaks of the resilience of Indian culture, while their symbolism continues to inspire seekers worldwide.

In essence, Hindu temples are special because they embody the eternal dialogue between humanity and divinity, matter and spirit, art and philosophy. They remain not just monuments of the past but living traditions, affirming India’s role as a cradle of spirituality and architectural genius.

.jpg)